Libertarians and classical liberals alike have always struggled to explicate or define their central concept, that of freedom.

As with any definition, there are three problematic outcomes:

Infinite regress

Circular definition

Aborting the definition

This is quite analogous to Hans Albert's famous Münchhausen trilemma on the problem of ultimate justification.1

A definition basically just wants to combine two different groups of words with the same meaning. The term to be defined is the term assumed to be not yet understood or to be explained in more detail. Put simply, the definition of the term is intended to explain the term to be defined using other, more familiar words. A tautology such as "A is A" is the most obviously misguided attempt of a definition, which immediately reveals its emptiness and therefore uselessness. This circularity is what one wants to avoid above all.

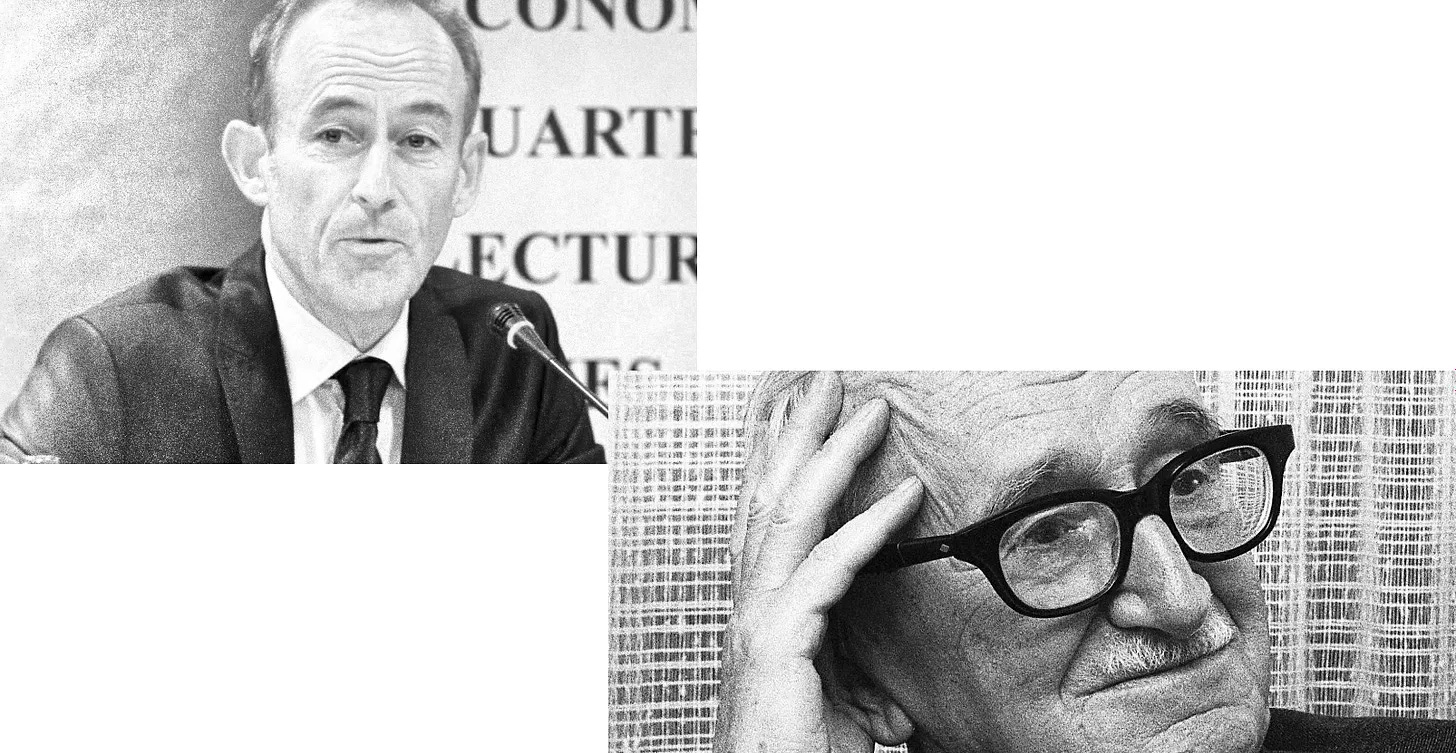

"Freedom is the absence of coercion" is probably the most common definition of freedom, as it has also been conveyed by classical liberal greats such as F. A. Hayek in the past. But libertarians such as Hardy Bouillon2 argued that this definition was circular and therefore worthless.

Indeed, further questions follow here - as with any other definition. For example, the question of what "coercion" is and whether freedom is maybe conceptually hidden in this term at some point. This is just one step backwards in the chain of definitions. It is the begin of the well known “regression of definition”. Here, at each step, at least one word explanation remains open. Or, at some point, one declares the explanatory word or the defining word group to be so fundamental and self-explanatory that it does not seem necessary or possible to explain it further or better. So one breaks off the chain, and arrives at its linguistic origin or simply cannot pursue it any further etymologically.

And that is indeed the case. A word at the origin of language cannot have been defined by other words, because there must have been a point in time (the original state) when there were no language and words and therefore no other words. The first word must have come into the world as a finger-pointing, recognizable, reusable sound. A shrill cry that points to a danger, perhaps a wild animal, that alerts the other members of a tribal community - until one day, after repeated use, the sound that has become specific perhaps stands for similarly recognized animals themselves. This is basically what all language is: sounds or sequences of sounds from intelligible, coordinating creatures capable of sound modulation; sounds that differentiate parts of an environment and point to these parts.

And no matter how long one extends these chains of defining sounds or meanings, they culminate in a gesture pointing at something or in a nothingness; in a meaningless nonsense that has lost its origin and become nothing but empty rhetoric. A danger to which the concept of freedom is more exposed than ever.

The libertarian or classical liberal concept of freedom is a negative one. This sets it apart from other, positive concepts of freedom. It is the absence of coercion, or more generally, of all undesirable influences mediated through language by others, interfering with one's sphere of action.

Hardy Bouillon attempts to eliminate the circularity of Hayek's definition of freedom by introducing a concept of "metachoice"(Metawahl). As an example, he refers to compulsory voting in Belgium. This presents people with a metachoice: either to go to the ballot box or pay a fine instead of voting. Bouillon calls the actual choice the "object choice". However, introducing another level like this is also not suitable for resolving the circle or solving the fundamental problem of any definition.

The actual coercion takes place solely on the level of Bouillon's 'metachoice.' It consists of the 'artificial costs' (Bouillon) incurred by rejecting the offer. And just as one must ask what coercion is, one must further inquire here what these 'artificial costs' are.

All costs are ultimately opportunity costs. When one pays a fine, the payer loses opportunities, namely the possibility of acquiring other things with that specific sum of money instead of their freedom from the ballot box. The very means of coercion is cost communication. The aim is to increase the costs of the undesirable option as high as possible so that a decision tips in favor of the preferred option. Coercion is a bending of will. And as such, it always involves a value judgment. Coercion is felt when this cost communication becomes obvious and compelling to the targeted actor.

In the end, one never escapes the circularity or the cessation of definitions. This is not exclusive to the definition of freedom; rather, it is inherent in the definitional process itself. The essence or actual content of any definition is ultimately imbued by its association with a primordial affect. In the case of liberalism, this affect centers around the sensation of being subjected, of experiencing external or alien determination. The determination of whether this sensation pertains to a state of subjection rests solely with the individual; otherwise, it would still constitute an alien determination and felt coersion. This elucidates the crux of the matter—no more, and no less.

Das "Münchhausentrilemma" oder: Ist es möglich, sich am eigenen Schopfe aus dem Sumpf zu ziehen?, Dr. Michael Schmidt-Salomon, Trier

Freiheit und Liberalismus im Wandel, Hardy Bouillon

J.C. Lester has an unusual approach. https://open.substack.com/pub/jclester/p/rule-of-law-meh?r=8hnjy&utm_medium=ios

If we despair about definitions, we face a dilemma. Either we must have coherent concepts without definitions, or we can’t argue coherently.